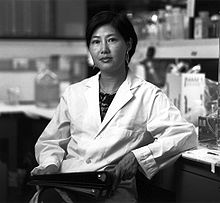

Mary Elizabeth Barber was a 19th century amateur scientist with no formal education. In 1820, her family moved to Cape Colony, South Africa where her love of natural history bloomed. It was the publication of the Irish botanist William Henry Harvey’s ‘The genera of South African plants, arranged according to the natural system’ and his request for specimens that began an almost 30-year correspondence with between Harvey and Barber. She became one of Harvey’s main suppliers of plants from South Africa, sending him approximately 1000 species with notes, illustrations, and assisting him with the naming and classification of numerous species. Her contributions resulted in several plant species being named after her. Barber started her entomology career documenting African moths and butterflies, sharing her discoveries with entomologist Roland Trimen who later introduced her to Charles Darwin. It is said that Barber indirectly influenced Darwin’s idea on the role of moths in orchid pollination. Ornithology became another interest of Barber’s and she became the first female ornithologist in South Africa, providing descriptions and depictions of birds for female sexual selection and gender equality. Mary Elizabeth Barber’s contributions were finally rewarded when she was invited and became a member of the South African Philosophical Society in 1878, became the first female member of the Ornithologischer Verein in Vienna (the main ornithological society of Austria), and had her contributions published by learned societies such as the Royal Entomological Society in London, the Royal Botanical Gardens in Kew, and the Linnean Society of London.  Nettie Stevens was a research scientist during the late 1800’s. She was interested in sex determination - how we end up either male or female. After earning her PhD in 1903, Stevens was the first to recognize that females have two large chromosomes in the shape of Xs and males have one large X and a small one chromosome resembling a Y. She also identified the Y chromosome in a yellow mealworm in 1905. Despite working towards a full researcher position at Bryn Mawr College, she was denied due to her sex. Instead, she was able to attain positions at leading laboratories and marine stations, where she published 38 chromosomal heredity papers, providing critical evidence for the chromosomal inheritance theory. Her research was not immediately accepted by the surrounding community. It wasn’t until Edmund Wilson reached the same conclusion and acknowledged Stevens that the results were widely accepted. Stevens was eventually offered her full researcher position at Bryn Mawr, but before she was able to begin, passed away at age 50 of breast cancer.  Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin was a British-American Astronomer and Astrophysicist. She is most know in the field of astronomy for proposing the first explanation for the composition of stars in 1925. At the age of nineteen, she won a scholarship to Newham College, Cambridge University. Her interest in astronomy began when she attended a lecture by Arthur Eddington who had observed and photographed the stars near a solar eclipse. She completed her studies at Cambridge University, but she was not awarded a degree because of her sex. She felt her only career option in Britain was to teach, so she applied for grants that allowed her to move to the United States. She soon met the Director of Harvard College Observatory, Harlow Shapley, and afterwards enrolled in Harvard’s graduate program in astronomy. Her PhD work was called “Stellar Atmospheres, A Contribution to the Observational Study of High Temperature in the Reversing Layers of Stars”. Astronomer Otto Struve would later call her thesis “undoubtedly the most brilliant PhD dissertation ever written in astronomy”. In this work, Payne-Gaposchkin was able to accurately categorize stars by their temperatures and ionization. After her dissertation was reviewed, astronomer Henry Russell dissuaded her from presenting her conclusion, as it contradicted the knowledge of the time. In 1929, he reached the same conclusion through different methods, and published his findings. While receiving some credit, Payne-Gaposchkin was not fully recognized for her work at the time. After receiving her doctorate, Payne-Gaposchkin stayed on at Harvard in lecturing positions. In 1956, she became the first female professor at Harvard, and the first woman to become department chair.  Joan Clarke was a Mathematician during World War II who helped crack the German Enigma cipher, which was thought to be unbreakable at the time. She completed the equivalent of a double-first bachelor’s degree in mathematics at Cambridge University, but was prevented from formally receiving a degree due to her sex. In 1939, she was recruited to work in the Government Code and Cipher School at Bletchley Park. Like most women at Bletchley Park, Clarke was assigned clerical duties; however, her intelligence quickly earned her a promotion to work as a cryptanalyst on a team headed by Alan Turing, who had designed a precursor to the modern day computer to break the Enigma cipher. Clarke worked alongside her colleagues, who considered her as their equal, to decrypt German navy ciphers in real-time. The efforts of Clarke and her colleagues resulted in military actions that saved thousands of lives of Allied troops. For her work, Clarke was appointed as a Member of the British Empire, but, due to the secrecy of this project, the true extent of Clarke’s contributions may never be known.  Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian Actress and Inventor. At age 18, Lamarr married Friedrich Mandl, a controlling husband with business ties to Mussolini and Hitler (both of whom frequently attended parties in the Mandl home). Mandl forced Lamarr to attend business meetings, where the attendees discussed military technology. Unbeknownst to her husband, Lamarr’s interest in science was sparked during those meetings. Lamarr eventually allegedly fled to Paris disguised as a maid to escape her husband, and began her acting career which spanned 20 years. Bored of the sexist roles in which she was cast, Lamarr began inventing as a hobby. In 1942, Lamarr and colleague George Antheil patented a jam-proof radio system for torpedoes, called the “Secret Communication System”, using knowledge she gained from sitting in at meetings with her ex-husband. This system changed the frequencies of radio waves to prevent decoding by the Germans. The technology was difficult to achieve at the time and took 20 years to be used by the US Navy, but was the basis for modern technologies we rely on, such as Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. In 1997, Lamarr was awarded the Electronic Frontier Foundation Pioneer Award and in 2014 was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.  Esther Lederberg was a Microbiologist who laid the groundwork for research on genetic inheritance in bacteria, gene regulation, and genetic recombination. She received her PhD in 1950 at the University of Wisconsin where her husband Joshua Lederberg was employed as an Associate Professor. Lederberg was the first to isolate the λ bacteriophage in 1951. She is also credited with the discovery of the bacterial F factor, used in sexual reproduction. Lederberg and her husband also developed a way to easily transfer bacterial colonies from one petri dish to another, called replica plating, which enabled the study of antibiotic resistance. The Lederberg method is still in use today. Her husband won a Nobel Prize in 1958 for that work, while Esther did not receive any of the credit. In 1974, after holding the position of Senior Scientist at Stanford, Lederberg was demoted to an Adjunct Professor position. She responded to this by founding the Stanford Plasmid Reference Center, of which she was the director, from 1976 to 1985.  Flossie Wong-Staal is a Chinese-American Virologist and Molecular Biologist. She was the first to clone HIV and determine gene function of HIV while working at the National Cancer Institute in the 1980s. This was a huge step in proving that HIV is the cause of AIDS. Dr. Wong-Staal went on to complete the genetic map of the human immunodeficiency virus, which made HIV tests possible. Wong-Staal also did fundamental research on the Tat protein associated with Kaposi’s Sarcoma that led to development of new treatments for patients with these dangerous lesions. She studied gene therapy using a ribozyme “molecular knife” to repress HIV in stem cells. This protocol is the second ever to be funded by the United States government. In 2007, The Daily Telegraph named Dr. Wong-Staal a well deserved 32nd member of the “Top 100 Living Geniuses”.

3 Comments

5/3/2017 12:35:32 am

Wow this is a really so good article is relating to science. Science is the very good filed and mostly student are joining this filed. Every student is need the good job and also spend the happy life with family.

Reply

12/9/2018 05:47:54 pm

Can I just say what a relief to find someone who actually knows what they’re talking about on the internet? You definitely know how to bring an issue to light and make it important. More people need to read this and understand this side of the story. I can’t believe you’re not more popular because you definitely have the gift.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Janosik LabWelcome to our lab blog. Members of the lab will write posts about current research, science or topics of interest. We look forward to your comments! Archives

December 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed